Introduction

Cheragh Academy is a public education platform that seeks to reduce sexual harassment in the workplace in Iran through public education and training. We envision a workplace without sexual harassment where all people are respected and heard. To that end, we organize free, online and certified sexual harassment trainings for employers and employees, regularly publish articles about sexual harassment on our website, engage and educate over twelve thousand Iranians on social media, and conduct original research.

In the spring of two thousand and twenty-one, the research team of Cheragh Academy’s board of writers decided to conduct a study on workplace sexual harassment in Iran. Very few studies have been conducted on this topic in Iran, and we wanted to contribute to the scholarship. Mainly, we wanted to understand to what extent our audience members experienced sexual harassment and if and how they recognized it happening in their workplaces. This inquiry prompted us to create a survey, publish it on the Cheragh Academy’s website and invite our audience to respond. This report captures our key findings. See Results starting on page five. (Download the PDF file of the report)

Background

In June two thousand and nineteen, at the International Labor Conference of the International Labour Organization (ILO), a new Convention (C190) and accompanying Recommendation were adopted, which explicitly stated that any violence and sexual harassment in the world of work was no longer tolerable and must end.

Although some countries, including Iran, have not ratified this Convention or implemented its recommendations in their labor laws or workplaces, this Convention remains a beacon of hope to those who live and work in those countries. It allows them to know their basic rights, even if they’re not able to exercise them at the moment. Awareness is the first step in implementing change and advocating for better working conditions. Furthermore, the existence of common global frameworks like the ILO Convention No. 190 can provide the key actors in the world of work (i.e., governments and their representatives) with new approaches and insights to prevent and address sexual harassment.

The new Convention and Recommendation states that everyone has the right to work in an environment free of violence and harassment, including sexual and gender-based violence and harassment. In fact, such a statement encompasses any type of workplace and that is why the term, “the world of work,” is important. “World of work” includes any type of workplace, from the formal and informal economy to rural and urban areas, and any social and cultural context or any economic, religious, and social conditions. In this Convention, “violence and sexual harassment” in the world of work refers to a range of unacceptable behaviors and practices or threats that aim at, result in, or are likely to result in physical, psychological, sexual or economic harm.

Article one of this Convention specifically refers to sexual harassment. Sexual harassment, which is a particularly common and negative phenomenon, threatens human dignity and the realization of equality in the workplace and society. It violates the rights of individuals, especially victims, and negatively affects their career advancement. Also, it upsets the gender balance in the workforce and widens the gender gap. These are just some of the consequences of sexual harassment in the workplace, and only from a social perspective.

Description

At present, there are no universal definitions for terms such as violence or sexual harassment in the workplace. This is mainly due to the fact that the world of work is still bargaining, negotiating, and standardizing these terms and concepts. This situation becomes even more difficult when we consider the social and cultural context of each country. Furthermore, different social contexts and workplaces create their own definitions of these concepts, which makes it even more difficult to come up with a universal definition. We have a long way to go before we reach a universal definition of these terms, but for right now, the best way is to use the definitions provided by international institutions and organizations.

Sexual harassment affects us unpleasantly in multiple ways. It tarnishes our dignity and can make us feel intimidated, humiliated, or insulted. In this study, sexual harassment is considered an unpleasant and unwelcome sexual behavior or gesture that affects a person’s performance in the workplace and creates a work environment that is intimidating, hostile, offensive, and irritating. Prior to completing the survey, the audience of Cheragh Academy was given this definition of sexual harassment and was informed about it.

In this study, sexual harassment is considered an unpleasant and unwelcome sexual behavior or gesture that affects a person’s performance in the workplace and creates a work environment that is intimidating, hostile, offensive, or irritating.

Validity of questions, reliability, and reporting of findings

Our survey set out to examine the incidence of sexual harassment among Cheragh Academy’s audience members. These are Iranians—women, men and nonbinary people—who have shown interest in and may have been educated on the topic by (one) reading articles we regularly post on our website and (two) engaging with social media posts and lectures we share on Instagram, Twitter and Telegram.

For our survey questions, we used the standardized questionnaire developed and used by international organizations for measuring sexual harassment in the workplace. This had two advantages for us: (one) the validity of our questionnaire was automatically verified because the questions were a) standardized and b) based on international experts’ opinions; and (two), we were able to conduct preliminary research on sexual harassment in the workplace. To ensure the reliability of the study, the questions were pre-tested and retested.

Ultimately, we sought to write this report in a way that could be used by different groups in Iran, including civil society groups, activists, academics as well as the general public. As a result, while we tried to simplify the findings as much as possible and avoided using specialized terms, we remained committed to reporting all of our findings to our audience.

We see our research here as a preliminary survey and a way to monitor changes in how the data about individuals with different backgrounds (age, education, workplace, etc.) who report their experiences of workplace sexual harassment in Iran will change over time. Given our deep belief in the need to investigate incidents of workplace sexual harassment through an in-depth review of experiences, we hope to use these preliminary findings in the near future to share interview-based findings and lived experiences of the victims of workplace sexual harassment. Some of these interviews have already been partially used in some articles published on Cheragh Academy’s website.

Information about respondents

Five hundred and ninety-seven people took part in the survey. Ninety-five percent were women (Five hundred and sixty five), four percent men (twenty seven) and one percent nonbinary (five). Respondents were a working age population, aged fifteen to Sixty-five.

Over ninety-seven percent percent of the respondents were between nineteen and fourty nine years old. About thirty percent of them were not working, while the rest were working. Nine of the respondents were having their first job experience. Three people stated that they did not have a job in the past and that they were not currently working. They were excluded from the study.

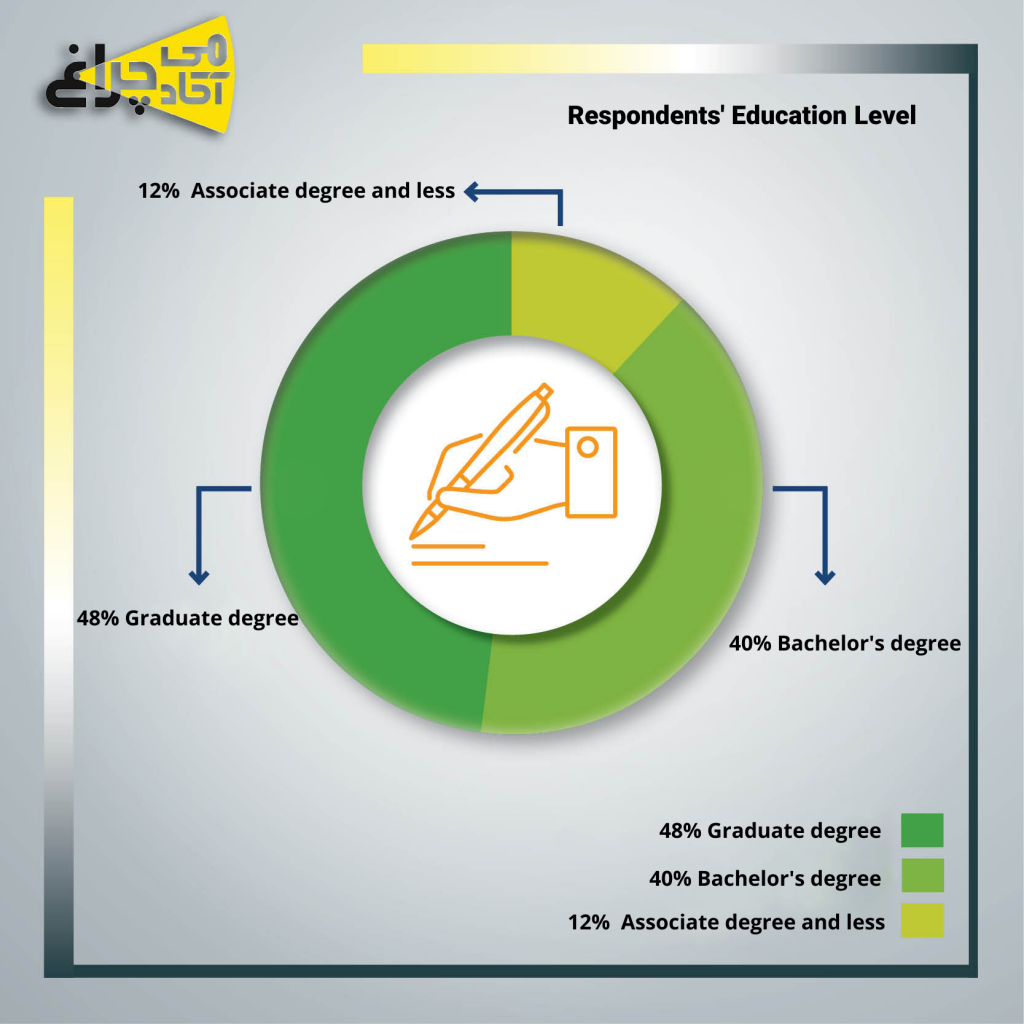

Participants with an associate degree and less comprised about twelve percent of the total respondents. Approximately forty-five percent of the respondents had a graduate degree and nearly forty percent of the other participants in the study had a bachelor’s degree.

Job distribution among respondents is approximately forty-three percent in the service sector, thirty percent

percent in industry, twenty percent percent in economy and trade, and seven percent in other economic sectors.

Fifty-seven percent of individuals rated themselves as having mid-level positions, nearly thirty-three percent as an employer or having a high-level position, and only ten percent rated their position as low-level.

Research Findings

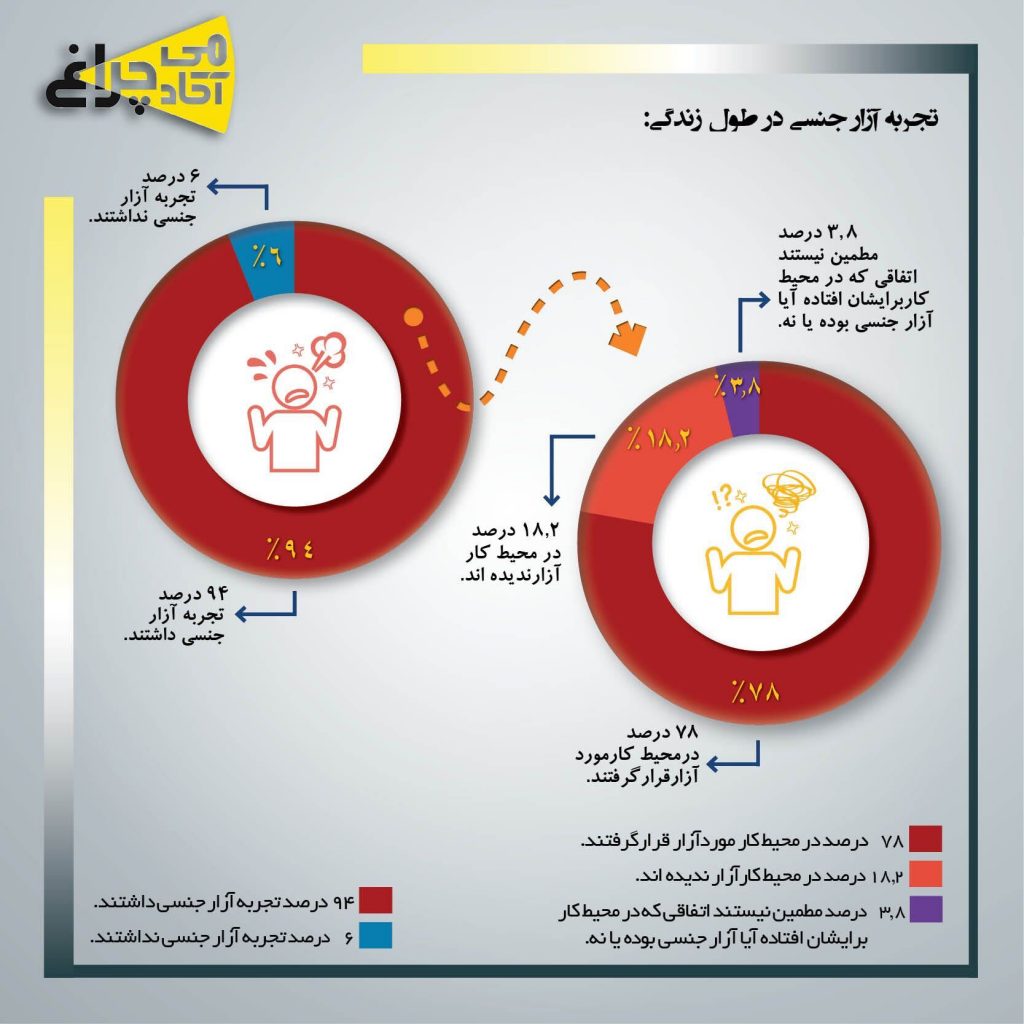

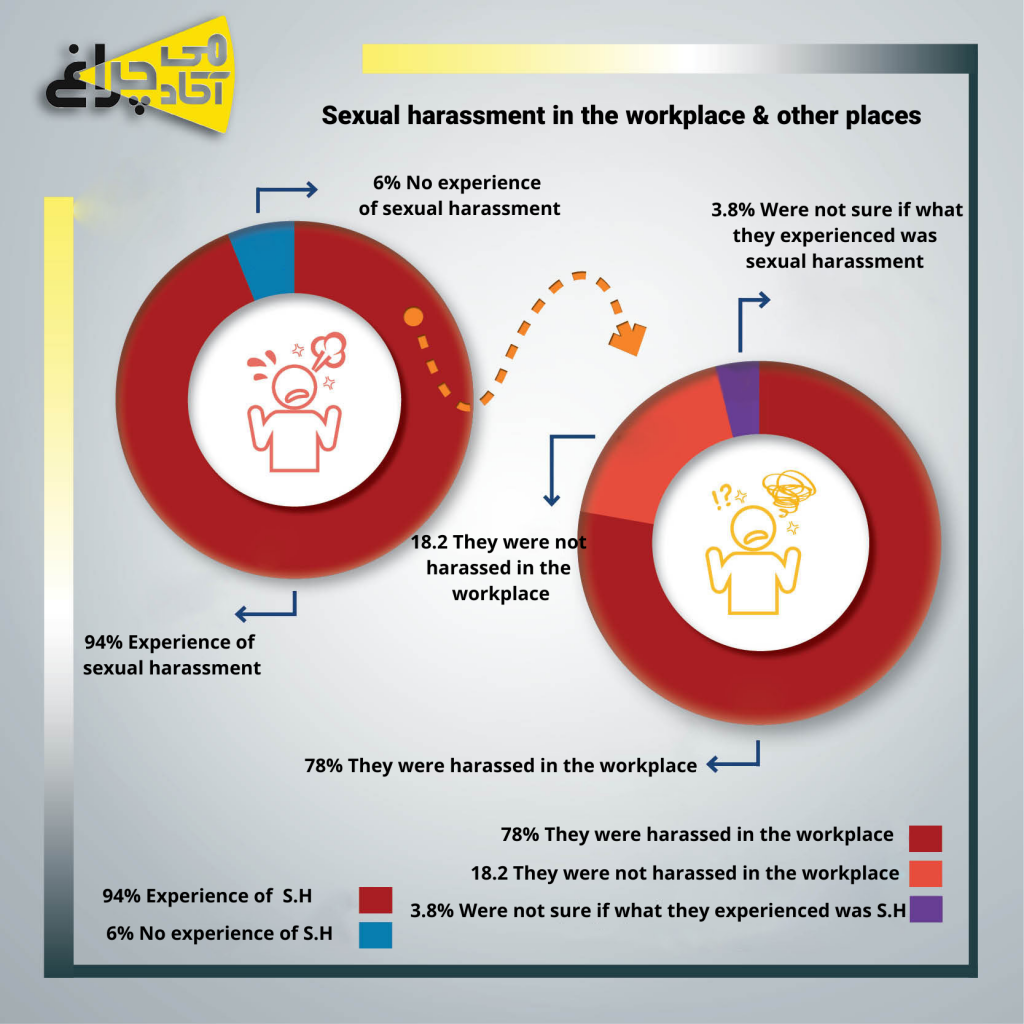

Before asking questions related to sexual harassment in the workplace, we asked a question about the experience of sexual harassment over the lifetime—school, home, neighborhood, public transportation, workplace and elsewhere. Of course, those who experienced sexual harassment in the workplace would also respond yes to this question. The opposite was also true: some people may not have experienced workplace harassment but they may have experienced harassment elsewhere. To examine this nuance, this question was included.

Seventy-eight percent of the people in the Cheragh Academy study experienced sexual harassment in the workplace.

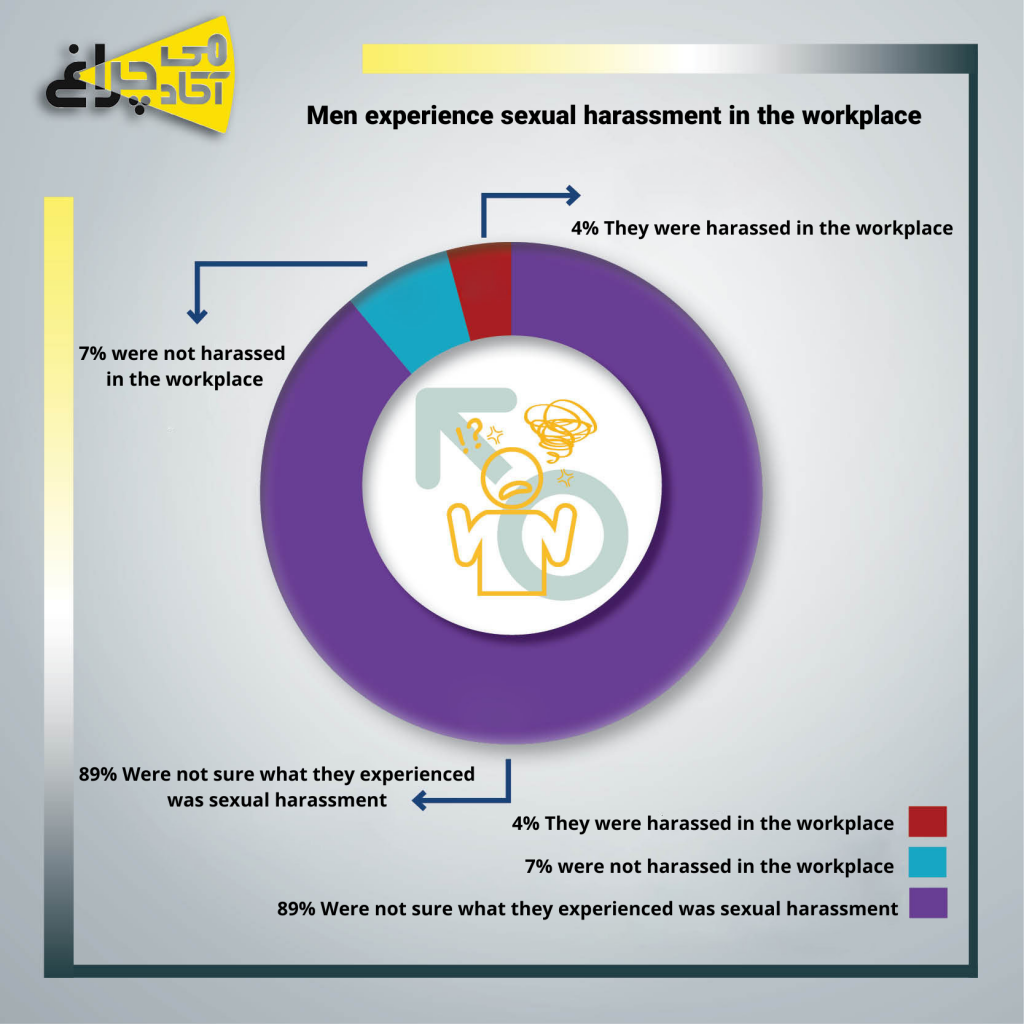

Although most of our respondents were women (ninety-five percent), the responses from a small number of male respondents and other genders were also interesting.

- ninety-four percent of the respondents stated (either with complete certainty or with some doubt), that they had experienced sexual harassment in their lifetime.

- Approximately six percent of the respondents indicated that they had never experienced sexual harassment, in life or the workplace.

- Interestingly, all of the respondents who were unsure whether they experienced sexual harassment or not were men. In fact, men did not have a clear definition of sexual harassment and continued to respond with uncertainty when they felt victimized. (Of the men in the study, two were confident that they had not been harassed, one was confident that he had been harassed, and twenty four men (eighty-nine percent) were not sure about the sexual harassment they faced).

- All respondents who defined themselves as nonbinary experienced sexual harassment in the course of their lives, but did not have a witness to corroborate it.

- Eighty-nine percent of the women in the study (five hundred and one of five hundred and sixty one women) had experienced sexual harassment in their lifetime (in general, not only workplace) and were confident that what they experienced was sexual harassment.

After considering sexual harassment in a general sense, we looked at sexual harassment specifically in the workplace. Of the respondents who experienced some form of sexual harassment in the workplace (with certainty or doubt):

- Seventy-seven percent were women.

- One percent were nonbinary individuals (all nonbinary individuals in the survey indicated that they experienced sexual harassment in the workplace).

- Three points eight percent were men and women who were not sure if what they experienced was sexual harassment (approximately equal numbers of men and women).

- Twenty percent of women surveyed did not experience workplace sexual harassment. Among the women who participated in the study, one hundred and seventeen women did not experience sexual harassment in the workplace, which, as mentioned earlier, does not mean that they had never been sexually harassed.

- In general, it can be said that eighty-five percent of the people who experience sexual harassment in society, also experience sexual harassment in the workplace.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained, if we consider the majority of respondents in this study as “educated, middle-class, young people engaged in the service sector,” we may be able to extrapolate these survey results to the general society in Iran, at least the service sector.

The findings from the survey of our audience also carries an important message: the issue of accessibility and the possibility of raising awareness about workplace sexual harassment. The fact is that much of awareness-raising efforts through social media, which we have been actively doing since we launched the Cheragh Academy, could be potentially insignificant for some industries, especially the ones that we do not have enough information and statistics about. ُThis is where the role of civil society and various activist groups is critical, as well as direct access to work environments regarding education, training and awareness raising among employers and employees.

This study also allows us to rule out the stereotypical belief that victims of sexual harassment are uneducated or unknowledgeable. In fact, college educated respondents were no better at recognizing sexual harassment than others, and were no less likely to fall victim to it than other groups.

Also, our findings disproved the myth that sexual harassment is less likely to occur in service-based work environments (such as education and medicine versus industrial and commercial environments). Specifically, as we have repeatedly reiterated in the articles published on Cheragh Academy’s educational website, sexual harassment is directly related to power.

On the other hand, we observed that more than eighty percent of the respondents have experienced sexual harassment both in the workplace and outside. In the upcoming reports, we will explore in depth the kinds of sexual harassment most people have experienced, but given the wide range of sexual harassment-related incidents, it can be concluded that a large number of Iranian employees does not feel safe from sexual harassment, not solely in their work environments but in society in general.

One of the most important findings of this section of the report is the difference in the number of respondents based on gender. The vast majority of survey respondents were women. We had a very low number of nonbinary people participate (five people). Perhaps one of the most important reasons—after lack of access—is the issue of fear. Because they’re discriminated against in the Islamic Republic of Iran, these persons do not trust any platform, even ours because they’re afraid of being “exposed” and their information revealed. Therefore, due to a small number of LGBTQI+ respondents, we could not draw any accurate and generalizable conclusions in this regard.

The findings regarding men in this study are significant. Men, despite their low participation, reminded us of an important issue: Iranian men lack awareness of what sexual harassment is. If we take a look at the findings on sexual harassment among men, we find that most of the male respondents were skeptical whether or not something unpleasant that had happened to them was indeed sexual harassment.

In fact, relying on patriarchal stereotypes that see men as “perpetrators” and as “subjects” of sexual harassment comes at a cost that makes it extremely difficult for men to accept and talk about sexual harassment. Such a situation turns men into victims of patriarchy because they subconsciously fear that their masculine identity will be affected by acknowledging that they have experienced sexual harassment.